Coaster Brook Trout

Summary

Coaster Brook Trout are a form of the eastern brook trout species Salvelinus fontinalis, once common in Lake Superior, but now comparatively rare. Along with lake trout Salvelinus namaycush, they comprise the two char species native to Lake Superior. Not a separate species or subspecies, coasters occur when environmental and habitat conditions are ideal and enable this species to fully exploit their evolutionary niche. These conditions once occured around most of Lake Superior. Today, healthy populations exist primarily in the Nipigon Bay region of Ontario. Small distinct populations also exist near Isle Royale and one in the Salmon-Trout River on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Currently, the population along Minnesota's north shore appears to be increasing.

Current Regulations

Minnesota Fishing Regulations 2024 state that all splake and brook trout in Lake Superior and tribuatary streams of Lake Superior below posted boundaries have a minimum size limit of 20", a possession limit of 1 (combined total brook trout, splake, brown trout and rainbow trout is 5), and an open season of April 13 to Sept 2. No treble hooks are allowed in tributaries of Lake Superior below posted boundaries. Additional regulations apply. MN Fishing Regulations Online 2024

Historical Abundance

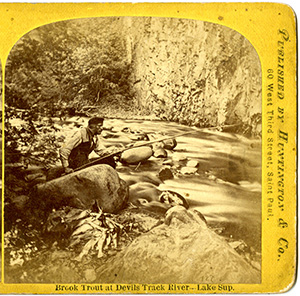

In 1875, British-born photographer William H. Illingson Jr. left his St. Paul studio and journeyed north to Duluth, Minnesota. There he boarded a steamship and sailed up the north shore of Lake Superior. He eventually disembarked at the fledgling village of Grand Marais, founded only a few years earlier. At the Devil Track River, three miles further up the shore, he made a series of remarkable photographs. Although undoubtably staged, he hiked upstream, photographed the rugged canyon and an unidentified angler, fishing the rapids for Brook Trout with a simple wooden pole. Several of the photographs show the angler with his catch, an impressive stringer of Brook Trout displayed upon a rock. Many of the Brook Trout are massive.

The catch was not that unusual. In fact, in the 1860s, Lake Superior was already a national destination for the pursuit of trophy Brook Trout, both in terms of numbers and size. Robert Barnwell Roosevelt, a New York politician and Teddy Roosevelt's uncle, chronicled his adventures fishing Lake Superior shores in his 1865 book, Superior Fishing.

Roosevelt writes of chartering a schooner and so he and his cronies could explore and fish at the mouths of rivers and streams along the Canadian shore of Lake Superior. Other anglers preceded them, and Roosevelt's party fished according to their recommendations. They camped at the Agawa, Batchawaung and Neepegon (Nipigon), among others. Their fly-fishing catches were exceptional. From an un-named brook, Roosevelt describes catching dozens of Brook Trout averaging three pounds apiece. Although the group did not go there, the book promotes the Bayfield area as the best of fishing where "two hundred and fifty pound weight of speckled trout have been killed in one day by one good angler and one bad angler." The Brule and nearby tributaries "although often choked with drift, are filled with fine trout."

Historic commercial fishing records document that Coaster (Coastal) Brook Trout spawned in at least 30 U.S. streams, including 11 in Minnesota. Undoubtably, they spawned in most streams. So good was the fishing that when a wagon trail was established in the 1880s along the Minnesota shore, with it came an influx of sport fishermen and the construction of fishing resorts. One such lodge was the Baptism River Club founded in 1886 at the mouth of the Baptism River by Duluth resident Charles H. Graves. Guestbook comments from the period record numerous Brook Trout in the five-pound range. However, by the 1920s the fishing was well in decline. The club responded with repeated stocking of Brook Trout, Rocky Mountain Trout (Rainbow Trout), Loch Leven-strain Brown Trout and steelhead-strain Rainbow Trout.

The Decline

The culprits for the decline were numerous. The high gradient streams of Minnesota's north shore still have a tendency for spate conditions of high flow in spring run-off and summer rain events. This was exacerbated as logging converted primarily coniferous forest of white and red pine into second growth cover of aspen and birch. Where winter snow cover was once shaded by pine, the bare-leafed deciduous cover accelerated spring run-off. Preferred Brook Trout habitat of cold, shaded water disappeared. Retired Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources fisheries specialist and Brook Trout expert Dennis Pratt has been able to correlate the decline of Brook Trout along the south shore in Wisconsin with the march of logging operations across the watersheds by comparing angler reports in local newspapers. Once the loggers went through, Brook Trout disappeared, and sport anglers moved on. Few commercial fisheries specifically targeted Brook Trout but overfishing by sport angers must have played a significant role, as catch-and-release was unheard of. Competition from other introduced species played a part as steelhead filled the niche created when Lake Trout were decimated by invasive lampreys. In the 1930s George Shiras, photographer for National Geographic Magazine lamented about the decline of Coaster Brook Trout, attributing the decline to logging, habitat degradation and impoundments. Although not significant on the Minnesota shoreline, the 1920s and 1930s saw dams built on the mightiest of Coaster rivers, the Nipigon.

In Minnesota, Coasters probably were never as plentiful as they were along Ontario, Wisconsin and Michigan shores. By the 60s and 70s, Coaster Brook Trout were a rarity in Minnesota. Remnant populations hung on in the waters of Isle Royale, along Canada's north shore, specifically in the waters of Nipigon Bay and near Michigan's Salmon-Trout River, west of Marquette. Here, in a battle against proposed mining in the Huron Mountains at the headwaters of the Salmon-Trout River, the Sierra Club and the Huron Mountain Club in 2006 unsuccessfully sued the Bush administration to list the Coaster Brook Trout under the Endangered Species Act.

The Recovery Begins

The late 1990s was a watershed moment in Coaster Brook Trout rehabilitation efforts. In 1999, the Great Lakes Fishery Commission produced "A Brook Trout Rehabilitation Plan for Lake Superior," which organized and coordinated Brook Trout rehabilitation efforts in Lake Superior. Participants included the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, the Department of Natural Resources in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, tribal agencies in the Lake Superior basin, Trout Unlimited, university researchers, and Minnesota Sea Grant. The most immediate result was an initiative to identify and protect remaining populations, through restrictive harvest regulations. In 1997, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources implemented a "one fish over 20 inches" minimum size limit, along with a closed season below the barrier of Lake Superior tributaries.

Various stocking and rehabilitation effort were initiated in the late 90s, primarily by the Grand Portage Band, the Red Cliff Band and the Keweenaw Bay Bands of Ojibway. The U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service began stocking programs in 2001 at Pictured Rocks National Seashore and Isle Royale. The Department of Natural Resources made various stocking attempts to rehabilitate Coasters in Minnesota, from the mid-1900s thru 1987 with minimal success. The Grand Portage Band program has been the most extensive. In 2007, the Grand Portage Band built its own fish hatchery with a vision of creating a self-sustaining run of about 20 pairs of adults in three streams on the reservation.

In 1997, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources began collecting data on Brook Trout in the tributaries below the barriers. Electro-shocking below the barriers has been conducted in the fall, during the spawning run about every five years. Around two dozen streams are assessed from Duluth to Grand Portage, although some streams are skipped, and some are visited more than once in each survey cycle.

The most recent assessment was autumn 2018, when Nick Peterson, Migratory Fisheries Specialist with the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Lake Superior Area Fisheries, led a group composed of fellow staff and volunteers from Trout Unlimited, Minnesota Steelheader, The Lake Superior Steelhead Association and The Greater Lake Superior Foundation. Together they sampled 12 streams, several more than once.

Comparing year-to-year results is difficult. The migratory nature of the population, fluctuating river levels and water temperatures affect the efficacy of the survey methods. Thus, these surveys are not estimates of a population but more of a snapshot. Roosevelt found the same phenomena, even when revisiting a river just a few weeks apart. He would have excellent fishing one day, leave and come back a week later and find the trout had vanished.

Rivers that have been less productive in previous surveys, such as the Cross and the Gooseberry held more fish in 2018. Fewer fish than were expected were found in other rivers, such as the Kadunce and the Kimball.

Nick's summary of the 2018 survey concludes that "Coaster Brook Trout populations on the North Shore have sustained or increased in abundance over the past two decades (at least since the first survey in 1997). The capture efficiency and abundance of Coasters at each river sampled appears to be influenced greatly by the local stream and environmental conditions each fall. The most recent surveys in 2013 and 2018 showed that Coasters are reaching older ages than was found in the first surveys (1997 and 2003), and that the Brook Trout are increasing in size over time, which correlates with increasing age structure over time."

Current Status

From an angler's perspective, it has become apparent that in the past decade the numbers, size and range of Brook Trout along the Minnesota north shore of Lake Superior has improved. Coasters are now being caught as far west as the Knife, although mid-shore streams such as the Poplar and Baptism are better rivers for finding Coasters. Steelhead anglers catch Coasters that are feeding behind spawning Steelhead. Shore casters working river mouths have been catching Coasters, and even mid-winter anglers, targeting Kamloops are catching a few. They are showing up in the Grand Marais Harbor. They range in all sizes, but 12 to 16 inches are possible, with a very few over 20. Coasters are being caught in the lower pools of rivers in mid-summer, especially after high water events. Granted, the probability of catching a Coaster is still slim, but it is possible. The increase in number and size is likely the result of the 20-inch minimum size limit introduced in 1997. The apparent increase in success may also in part be from an increased awareness due to social media and advocacy from groups like ourselves, Minnesota Steelheader and Minnesota Trout Unlimited.

Some caught fish are fin-clipped fish, which indicates that they are strays from stocking programs in Grand Portage or Redcliff. Many could be Brook Trout which were hatched above the upstream barriers and have migrated out for reasons unknown, such as high-water events or environmental conditions. If this is the case, upper river habitat projects like those sponsored by Trout Unlimited on the upper Sucker, and those by the Lake Superior Steelhead Association on upper Knife tributaries may have beneficial consequences. Some may be the progeny of Coasters that are successfully spawning below the barriers in the larger streams.

New Research Initiatives

To answer these and other questions to help advance rehabilitation efforts, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources initiated a Coaster Genetic Study in 2018.

Also led by Nick Peterson, this study uses trained volunteers to catch, sample and release Coasters using angling techniques. The anglers measure the fish, take a scale sample and finally clip the left pelvic fin to take a tissue sample for further genetic analysis by Dr. Loren Miller of the University of Minnesota.

The study will determine the genetic contribution to wild fish from Coaster hatchery strains and Splake (Brook Trout X Lake Trout hatchery hybrid). This is a growing concern among Lake Superior management agencies. The ongoing genetic evaluations will also meet multiple objectives defined in the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Lake Superior Management Plan for Coaster Brook Trout, help monitor impacts of various stocking strategies by other agencies, and support research on Coaster Brook Trout in Lake Superior.

The Future

Fishing for Coaster Brook Trout has not been better in generations. Although challenging, you can again - after decades - catch, admire and release one of these beauties in Minnesota tributaries to Lake Superior. But that doesn't mean the future is guaranteed. Dedicated interest in Coasters by both anglers and fisheries managers is expanding our understanding of the factors that influence their abundance. As Lake Superior and its tributaries reflect changing temperatures and precipitation patterns, experts expect this iconic species and other coldwater fish to live under increasing stress. Although we may never be able to achieve a return of Lake Superior Coasters to the numbers seen by Illingson or Roosevelt, preserving a beautiful native fish in Lake Superior for future generations is an aspiration that can excite and unite anglers.